The Home of Bond

“I wanted a really flat, quiet name… I thought that ‘James Bond,’ now that’s a pretty quiet name.”

In celebration of No Time To Die, Blackwell Rum is delighted to announce that it has partnered with the 007 film franchise.

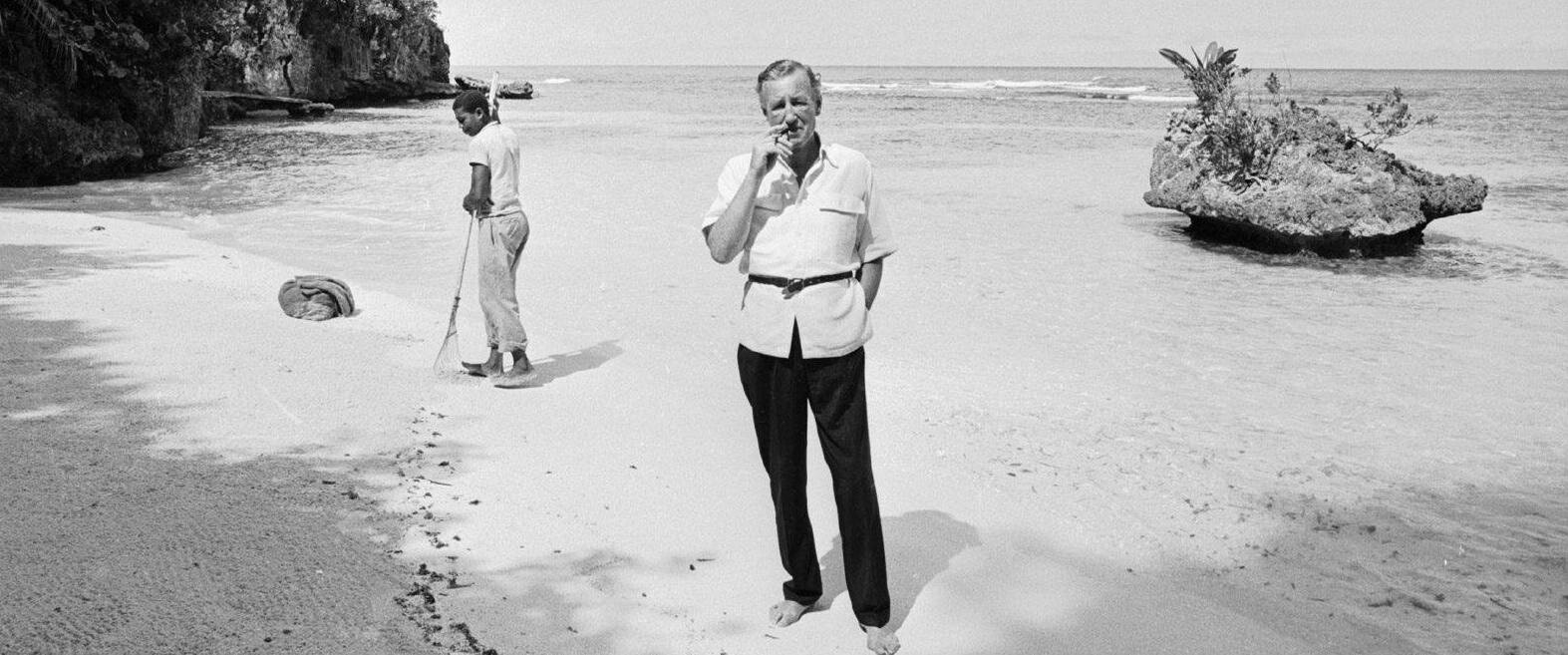

In 1942, an Anglo-American intelligence summit took Fleming to Jamaica. Impulsively, he declared that he would return to the island after the war and make it his home for life. Drawing on his Fleet Street years writing news coverage and his bureaucratic years of writing intelligence reports, he turned his talent to creating his enduring espionage hero, James Bond — a larger-than life version of Fleming, himself. The clothes were better. The gadgets were more dramatic. But Fleming rivaled Bond for pithy one-liners and romantic conquests.

So it was here, in Jamaica, in the romantic, tropical, exotic surroundings of Oracabessa Bay, that Fleming’s imagination — and hard work — took hold. Sitting at his plain wooden desk, in a corner of the villa that he’d designed for himself, Fleming wrote every one of the 14 books that made James Bond the name that is now recognized in every corner of the planet. James, the most common of English names… Bond, a synonym for reliability, or an upscale street in the heart of Mayfair… But in fact, in whimsical fashion, Fleming simply lifted the name of an English ornithologist — the author of “Field Guide of Birds of the West Indies” — for his iconic, unforgettable, masculine hero.

GoldenEye has a rich and colorful history. Rather than tell you, let us show you!

1939

Ian Lancaster Fleming is recruited by Her Majesty’s British Naval Intelligence.

1942

Periscope up! Nazi U-boats in the Caribbean? Commander Fleming is sent to investigate, working on a naval operation called GoldenEye. The beauty of the place and its people made it difficult for the 34-year-old to keep his mind on the fighting. He knew that when the war ended, he’d return.

1946

Fleming discovers that 15 acres of tropical overbrush, formerly a donkey racetrack, is for sale in the small, buzzy banana port town of Oracabessa Bay, Jamaica. Fleming telegraphs the local realtor, “PRAY PAUSE NOT. IAN”. Fleming sketches his dream villa on desk blotter, naming it, GoldenEye. He returns to dream up his super agent 007, James Bond.

1949

After falling in love with Jamaica on a visit to GoldenEye, playwright Noël Coward builds a beach home nearby, Blue Harbour. But besieged by a never-ending parade of glamorous guests, Coward buys an escape from his escape, a few miles up the hill from GoldenEye. Coward christens his new retreat, Firefly.

1950

The acclaimed travel writer, Patrick Leigh Fermor, visits GoldenEye. He writes: “Here, on a headland, Commander Ian Fleming has built a house called GoldenEye that might serve as a model for new houses in the tropics. Trees surround it on all sides except the sea, which it almost overhangs. The windows that look toward the sea are glassless, but equipped with outside shutters against the rain: enormous quadrilaterals...tame the elements, as it were, into an ever-changing fresco of which one can never tire.”

— The Traveller’s Tree: A Journey rough the Caribbean Island

1952

Typing out 2,000 words a day, Fleming writes Casino Royale, the first of his 13 James Bond novels, all of which were written in his bedroom at GoldenEye. Three of the books — Dr. No, Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun - are set in Jamaica.

1955

After attending school in England, Chris Blackwell returns to Jamaica where his family has lived since the 18th century.

1956

Britain’s Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden and his wife spend three weeks at GoldenEye. Eden writes to Fleming:“I do not think that there is any other place anywhere that could have given me the rest I have to have. The bathing, the beach, the seclusion, the size of the grounds were all just perfect to enjoy and be concealed.”

Before leaving, Eden plants a tree in the garden at GoldenEye— inaugurating a custom that continues today.

1959

After returning to the Jamaica of his childhood and following stints as an aide de camp to the governor then as a waterskiing instructor, Blackwell records blind pianist Lance Heywood, whom he first heard perform at the Half Moon resort. This recording session begins the story of Island Records. A brilliantly independent label just off the coast of the music industry, Island did more to change the cultural landscape than any record label in history. Island Records brought reggae music to the world outside Jamaica, with Blackwell himself producing Bob Marley and the Wailers. Island broke British acts like Traffic, Bad Company, ELP, Free, Fairport Convention, King Crimson and the greatest of world music from the Irish traditionalists The Chieftains to Africans like King Sunny Ade. It brought us such independent spirits as Roxy Music, Brian Eno, Sparks, Grace Jones, Marianne Faithfull, Tom Waits and that Irish band, U2.

1950s - 1960s

The sexy social vibe of Jamaica’s North Coast seduces Errol Flynn, Lucian Freud, Katharine Hepburn, Cecil Beaton, Laurence Olivier, Evelyn Waugh, Alec Guinness, John Gielgud, Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Sophia Loren and Truman Capote. Enchanted, the smart set whirls among Fleming’s GoldenEye, Coward’s Firefly and Blanche Blackwell’s house, Bolt.

1961

Dr. No, the first Bond novel made into a film, is shot in Jamaica. At Fleming’s suggestion, Chris Blackwell is hired as a location scout and consults on the movie’s soundtrack.

1962

My boy lollipop! You make my heart go giddy up.

Blackwell produces “My Boy Lollipop.” Six million copies sell worldwide. Jamaican singer, Millie Small, rockets to stardom. Island Records has arrived. A brand new beat takes over popular music.

Jamaica, land we love, Jamaica, land we love.

On August 6, 1962: Jamaica declares itself and independent country.

1964

Playboy publishes the last interview with Fleming. In it, he explains the inspiration behind the name of his villa: “I had happened to be reading Reflections in a Golden Eye by Carson McCullers, and I’d been involved in an operation called Goldeneye during the war: the defense of Gibraltar, supposing that the Spaniards had decided to attack it.” Fleming passes away on August 12th.

1965

The Bullshot is the cocktail du jour. Coward tells Queen Mum, “You must try one!” Queen Mum obliges and drops in for a drink at Firefly while visiting Jamaica.

The Bullshot:

3 oz. vodka

4 oz. strong cold beef bullion

salt and pepper

1972

Island Records releases Bob Marley and the Wailers, Catch a Fire in the now-famous Zippo-lighter record sleeve. Marley becomes a superstar, igniting the “rebel romance” of Jamaica around the world.

1973

The Harder They Come, the film starring Island Records reggae singer Jimmy Cliff hits the screen. Love Jamaica? This is a must-see!

1974

American writer and journalist Jon Bradshaw publishes Backgammon: The Cruelest Game following many heated games at GoldenEye.

1976

Chris Blackwell buys GoldenEye. “I thought of living there,” he says, “but I never did—I just went there sometimes, swam there sometimes, let friends and family stay there sometimes. You could say it was a house I used as an entertaining place.” Watch Chris Blackwell talk about GoldenEye here!

1982

Dickie Jobson directs the film Countryman. Blackwell produces. Many cocktails are consumed at GoldenEye while discussing the details.

1983

The Police top the charts with “Every Breath You Take.” The song was written at GoldenEye while Sting was vacationing.

1989

Blackwell sells Island Records and founds the Island Outpost group of boutique hotels, buying the Marlin in Miami’s South Beach and kicking off the fabled city’s rebirth as a hip destination.

1998

Blackwell founds Palm Pictures, releasing the innovative, poetic music often heard at GoldenEye, including Ernest Ranglin, Baaba Maal, Gigi, Sidestepper and many more.

2002

Bono inducts Blackwell into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

2004 - 2006

Blackwell is awarded the Order of Jamaica medal from Governor-General Sir Howard Cooke and receives the International Humanitarian Award from the American Friends of Jamaica.

2007

Having already added 25 acres to the original 15-acre estate over a period of 30 years, Blackwell announces plans to add cottages and huts to the mix of villas that make up GoldenEye.

2008

The Jamaica Observer asks Blackwell, “What was the inspiration for your great and uniquely Jamaican hotels?” Blackwell expounds, “I focus on finding stunning locations and then putting hotels on them.... I try to turn people onto the natural beauty of Jamaica and encourage them to meet its people.”

2009

IN APRIL, Music Week names Blackwell “Most influential U.K.- based industry executive of the past five decades.”

IN MAY, Island Records celebrates 50 years with a string of concerts.

2010

GoldenEye closes for major renovations.

2011

GoldenEye garners accolades and acclaim: Travel + Leisure puts it on their “It List: Best New Hotels 2011,” the World Travel Awards put it on their “Hot List: Best New Hotels & Resorts of 2011,” and Smart Luxury Travel names it the Caribbean’s Number One Boutique Hotel.

Ian Fleming International Airport, located about five miles down the road from GoldenEye, is named for the area’s world-famous literary star.

2016

GoldenEye introduces...the Beach Huts! Blackwell fell in love with the beach hut concept on a trip across Jamaica back in the 1980s. Now, he’s built a hamlet of huts. All are designed so you feel one step away from sleeping under the stars.

© 2020 DANJAQ AND MGM. NO TIME TO DIE, 007 AND RELATED JAMES BOND INDICIA. © 1962-2020 DANJAQ AND MGM, NO TIME TO DIE, 007 AND RELATED JAMES BOND TRADEMARKS ARE TRADEMARKS OF DANJAQ, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.